Biography

A glimpse into the life of Umberto Eco: from his formative years in Alessandria and Turin, through his cultural engagement during the Milan years, to his teaching in Bologna and his literary achievements.

Brief biography

Excerpts from an intellectual autobiography

Umberto Eco knew how to inhabit many worlds — academia and popular culture, philosophy and fiction — with the rigor of a philologist and the lightness of a melancholy irony. He left behind an intellectual legacy built on method, curiosity, and a passion for knowledge understood as both the demystification of ideology and a practice of freedom.

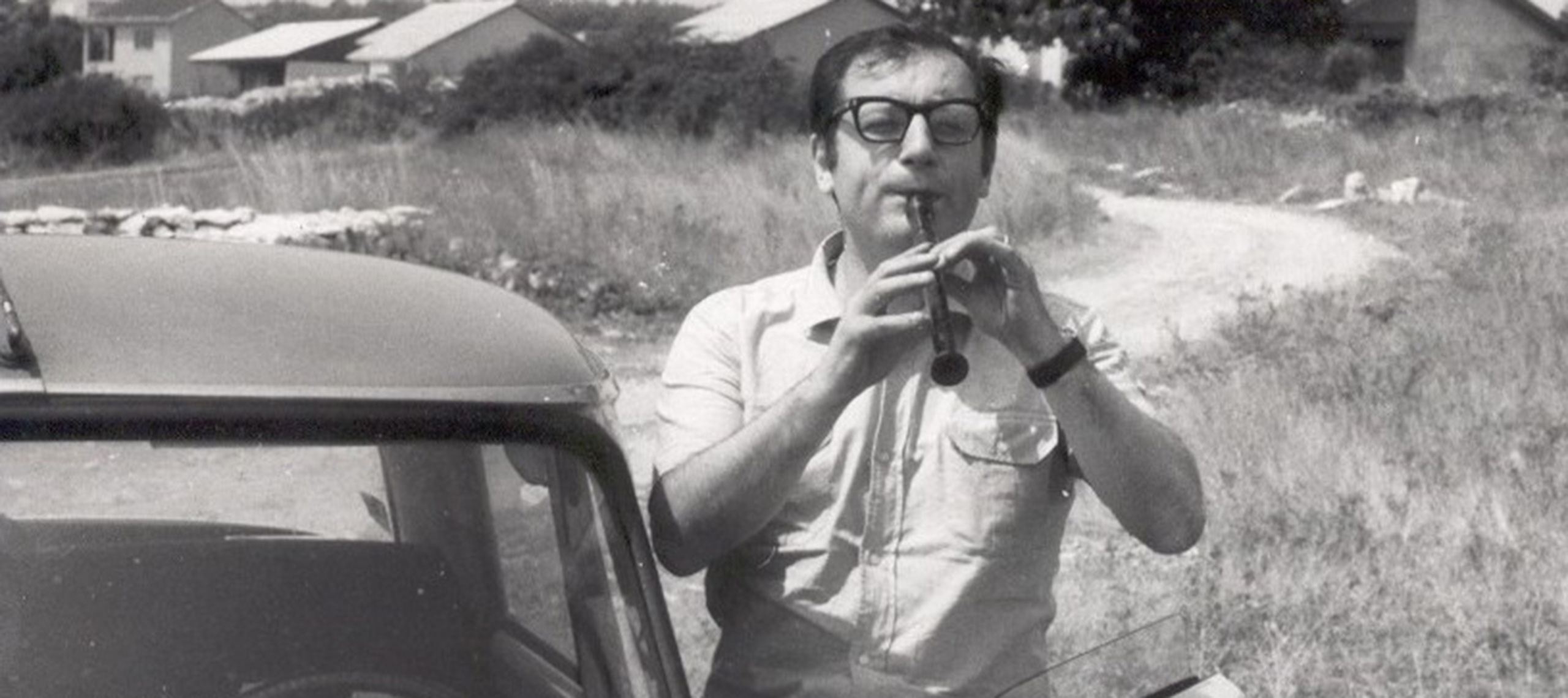

Born in Alessandria to Rita and Giulio Eco, Umberto Eco (1932–2016) has been one of the most influential intellectuals of the late twentieth century. His education was rooted in the philosophical tradition of Turin, particularly in the school of Luigi Pareyson, under whose supervision he graduated in 1954 with a thesis on Thomas Aquinas. The Middle Ages would remain a constant in his thought — not only as a field of study, but as a symbolic workshop of narrative structures, mythologies, and worldviews.

With the seminal Opera aperta (The Open Work, 1962), Eco inaugurated a new approach to the interpretation of art and literature, differing from the still prevalent teachings of Benedetto Croce, in dialogue with the neo-avant-garde, information theory, and structuralist thought. This was followed by other foundational studies such as La struttura assente (The Absent Structure, 1968), Trattato di semiotica generale (A Theory of Semiotics, 1975), and Lector in fabula (1979). Building on the semiotic theories of American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, these works established Eco’s international reputation as a theorist of signs, interpretation, and communication processes (I limiti dell’interpretazione — The Limits of Interpretation, 1990). Eco believed that reality exists independently of us, but that we can only access it through interpretative filters and textual mediation. In Kant and the Platypus (1997), this idea developed into a critique of both radical relativism and the dogmatism of naïve realism — a call for balance between the existence of an external world and the multiplicity of its interpretations. By excluding interpretations that are demonstrably false, we can approach reality through trial and error, guided by signs, concepts, and socially mediated languages.

Eco was also a pioneer in the study of mass media. In the 1950s, he worked as a cultural editor for RAI, Italy’s national broadcaster, where he encountered experimental artists and intellectuals such as composer Luciano Berio, with whom he collaborated on the programs of the Studio di Fonologia Musicale. This experience nurtured his interest in contemporary forms of communication and anticipated his involvement in Gruppo 63, the literary avant-garde movement that sought to transcend traditional narrative structures, echoing the ideas already explored in Opera aperta. His editorial work was equally crucial: beginning in the 1960s, he worked at the publishing house Bompiani, where he met his wife Renate the mother of their children, Stefano and Carlotta. There, Eco helped modernize the catalogue and introduced some of the most important voices in contemporary philosophy and the humanities to Italian readers. This editorial and public-facing engagement fed his lifelong dialogue with mass culture, which he later cultivated with brilliance and irony through his long-running column La bustina di Minerva in L’Espresso, where he reflected with wit and precision on language, politics, culture, and technology.

Worldwide fame came in 1980 with The Name of the Rose — translated into over forty languages and published in more than sixty countries — a novel that fused medieval mystery, theology, semiotics, and detective fiction. A philosopher “who also happened to write seven novels,” Eco went on to publish Foucault’s Pendulum (1988), a dizzying journey through esotericism and conspiracy; The Island of the Day Before (1994), a baroque meditation on time, fiction, and science; Baudolino (2000), a wise and playful voyage into the fantastic Middle Ages; The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana (2004), a visual and autobiographical novel about memory as a cognitive filter; The Prague Cemetery (2010), a fierce historical critique of modern antisemitism; and Numero Zero (2015), a lucid analysis of the mechanisms of information — an early warning against the rise of fake news and the chaotic, authority-less encyclopedia of the web. Throughout his life, Umberto Eco reflected — seriously, but never solemnly — on the act of storytelling and the thousand ways of reading, dismantling, and reconstructing it. With sharpness and irony, he crossed genres, languages, media, and centuries of history and literature, suggesting countless ways to wander among books. His work teaches us that storytelling is not only about saying, but about choosing, composing, and sharing spaces of meaning — and that to truly read is, in itself, a revolutionary act of freedom.

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

I was born in Alessandria, in the north west of the Italian peninsula. From the character of my fellow citizens I have learned the virtue of skepticism: despite their origins and the prowess they showed in resisting the Emperor’s siege, they never had any enthusiasm for any heroic virtues. (…) Skepticism implies a constant sense of humor to cast doubt even on those things that people sincerely believe in. It could be that this explains many cases in which I have waxed ironical about, or even parodied, texts on which I had written with great conviction. Born in 1932, I was educated under the fascist regime. I couldn’t understand, but I understood everything in the space of a few minutes on 27 July 1943. On the previous day fascism had fallen, Mussolini had been arrested and that morning, all of a sudden, newspapers I had never seen before appeared on the newsstands. Each one carried an appeal signed by the various parties, which were celebrating the end of the dictatorship. You didn’t have to be particularly smart to realize that those parties had not been formed overnight, they must have existed before, but evidently in clandestine form. I suddenly realized the difference between dictatorship and democracy and that, at eleven years of age, marked the beginning of my repugnance for any form of fascism.

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

My interest in philosophy began in high school, thanks especially to an extraordinary teacher, Giacomo Marino, who, along with history and philosophy, talked to us about literature, music and psychoanalysis. Together with Marino, Delmo Maestri and Giancarlo Lunati, two friends four years older than me (and who graduated when I started as a freshman), had a great influence on my philosophical development (…). But as soon as I arrived at Turin University I came into contact with other schools of thought. The teaching staff was made up of a group of philosophers who were very different from one another: Augusto Guzzo, who was generally classified as a Christian spiritualist although he defined himself as an Augustinian idealist (apart from his own ideas, he was also a masterful popularizer of other people’s ideas); Nicola Abbagnano, who was considered the leader of a “positive existentialism”, but in reality tended more and more towards certain trends in American philosophy and in any case was the head (also in terms of academic politics) of what was then defined as Neo-Enlightenment; Norberto Bobbio, under whose supervision I sat an exam on Rousseau before he wrote a book that greatly influenced me, Politics and Culture; and Carlo Mazzantini, an outstanding medievalist (…). In my second year at Turin University Luigi Pareyson was appointed full professor of aesthetics. His lessons were fascinating, they were not theatrical like Guzzo’s, not skeptically ironic like Abbagnano’s, but extremely rigorous, of a lucid, brilliant pedantry. So I decided to do my doctoral dissertation with Pareyson on the problem of aesthetics in Aquinas. It was my way of understanding medieval philosophy while tackling contemporary problems in aesthetics at the same time.

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

In working on Aquinas my intention was to show that the ancient world and the Middle Ages had reflected on the beautiful and on art (albeit in ways that differ from modern and contemporary philosophy) and the task I set myself was to free the medieval thinker from all the Neo-Thomist interpretations that, in order to demonstrate their “modernity”, had tried to make him say what he had not said. In those same years this polemic came to coincide with certain events that changed my life. A militant Catholic and a national leader of the youth branch of Azione Cattolica known as Gioventù Cattolica, I was (together with my comrades) still influenced by the personalism of Emmanuel Mounier and Esprit, which led us to be, as they said in those days, “left-wing Catholics” — and in any event anti-fascists. So I was one of those “rebels” who in 1954 left the organization in protest against the support Pope Pius XII was giving to Luigi Gedda, the president of Azione Cattolica, who was leading the organization towards the far right. This matter, which many of my comrades of those days held to be solely political, was gradually turning into a genuine religious crisis for me. (…) The thesis had begun as an exploration of a territory I still considered to be contemporary and then, as the inquiry proceeded, the territory was objectified as a distant past, which I reconstructed with fondness and enthusiasm, but the way you do with the papers of a deceased person you have greatly loved and respected. And this result derived from my historiographical approach, where I decided to clarify every term and every concept found in the medieval texts with reference to the historical moment in which they were expressed. In order to be truly faithful to Aquinas, I restored him to his own time; I rediscovered him in his authentic appearance, in his “truth”. Except that his truth was no longer mine. All that I inherited from Aquinas was his lesson of precision and clarity, which remained exemplary.

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

(…) At the end of 1954 I had moved to Milan when I got a job in the cultural program section of the newborn television service. In television I came into contact with a communicational experience that was new at the time, and I had published in the Rivista d’estetica an article on television and aesthetics. But this was not the only aspect of the mass media I was interested in: I was also into comic books and other aspects of popular art and in the early Sixties I had published a piece in praise of Schultz’s Peanuts that was translated into English many years after by the New York Review of Books. (…) In those corridors I chanced to bump into Igor Stravinsky and Bertolt Brecht. In short, it was an experience that was fun more than anything else and left me a lot of free time in which to continue my studies. I broke off my work in television to do my military service and immediately after that I started work as an editor with the Bompiani publishing house, then run by the great publisher Valentino Bompiani. (…) The seventeen years spent at Bompiani were valuable for my philosophical activity. First of all, almost immediately the publisher put me in charge of the “Idee nuove” (New Ideas) series. It was a famous series that, even before World War II, and getting around fascist censorship, had published many important European authors, over and above the then dominant Crocean idealist tradition: it should suffice to mention names such as Spengler, Scheler, Simmel, Santayana, Jaspers, Abbagnano, Berdiaeff, Hartmann, Ortega y Gasset, Unamuno, Bradley, Windelband and Weber. When I took over the series, the Encyclopedia of Unified Science had just brought out an anthology of its principal texts. Among the authors I later had published I should mention works by Arendt, Barthes, Gadamer, Lotman, Paci, Merleau-Ponty, Goldmann, Whitehead, Husserl, Sartre, Hyppolite, Reichenbach, Tarski and Baudrillard, as well as other Italian authors and various collections in Italian of the works of Charles S. Peirce. But in parallel with this series I had also started up a series that was to publish various works on cultural anthropology, psychoanalysis and psychology (Fromm, Kardiner, Jung, Binswanger and Margaret Mead). In subsequent years I also started up a series on semiotics that featured, as well as many Italian scholars, texts by Jakobson, Greimas, Lotman, Goffman. In the Seventies I also founded the magazine VS – Quaderni di Studi Semiotici (which is still published) in which I invited contributions from authors from various countries, published also in French and English. Working for a publishing house allowed you to consult all the book catalogs from a variety of countries: so working for a publisher was like living in an extraordinarily up-to-date library. (…)

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

To understand the birth of The Open Work I have to take a step back and return to the four years I spent in television. At that time the top floor of the radio and television building housed the music phonology laboratory run by great musicians such as Luciano Berio and Bruno Maderna, who conducted the first experiments in electronic music. The laboratory was frequented by musicians such as Boulez, Stockhausen and Pousseur and the encounter with the problems, the practices, and the theories of post-Webern music was fundamental for me, also because those musicians were interested in the relationship between the new music and linguistics. It was through Berio that I then met Roland Barthes and Roman Jakobson, and it was in Berio’s magazine, Incontri musicali, that there were published discussions between a structuralist linguist like Nicholas Ruwet and a musician like Pousseur, and I began to publish the first essays of the book that in 1962 would become The Open Work. Finally, in Milanese circles the new magazine Il Verri had come into being while the meetings and discussions on art and literature that were to give rise to the Gruppo 63 — a community of writers and artists of the new avant-garde — were already taking place. So that was the situation for a young scholar of aesthetics, who since high school had had contacts with the first “modern” poetics, and who found himself stimulated both by the practices of the avant-garde and those of mass communications. I did not maintain that these two aspects of my research were separate, and I was looking for a point of fusion between the study of “high” art and that of the art held at the time to be “low”. And if the moralists who were insensitive to the new times accused me of studying Mickey Mouse as if he were Dante, I replied that it is not the subject but the method that defines the correctness of research (and, moreover, a good use of method makes it clear why Dante is more complex than Mickey Mouse and not the other way round). Pareyson’s thinking had helped me to distance myself definitively from Croce’s aesthetics. (…) There was, however, an aspect of Pareyson’s aesthetics that I did not accept (and it was this divergence that provoked our long-lasting period of mutual incomprehension). Since Pareyson’s idea was that the theory of interpretation concerned not only artistic forms, but also natural ones, for him interpreting a form involved presupposing a Shaper who has constituted the natural forms specifically as cues for possible interpretations. Conversely, I thought that the entire theory of interpretation could be “secularized” without a metaphysical recourse to the Shaper, who at best can be postulated as a psychological support for those who embark upon the adventure of interpretation. In any case, from Pareyson’s theory of interpretation I got the idea that, on the one hand, a work of art postulates an interpretative intervention; but, on the other hand, it exhibits formal characteristics in such a way as to stimulate and simultaneously regulate the order of its own interpretations. That is why, faced with the unavoidable presence of the form to be interpreted, years later I insisted on the principle that perhaps it is not always possible to say when one interpretation is better than others but it is certainly always possible to say when the interpretation fails to do justice to the interpreted object.

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

In 1962 in The Open Work I was advocating the active role of the interpreter in the reading of artistic texts (and not only verbal ones). In a way it was one of the first attempts to elaborate what was later defined as reception aesthetics or reader oriented criticism. (…) To say that the interpretations of a text are potentially unlimited does not mean that interpretation has no object. Even if we accept the idea of unlimited semiosis, to say that a text potentially has no end does not mean that every act of interpretation has a happy ending. This is why in The Limits of Interpretation (1990) I proposed a sort of Popper-like criterion of falsification whereby, while it is difficult to decide if a given interpretation is a good one, and which of two different interpretations of the same text is better, it is always possible to recognize when a given interpretation is blatantly wrong, crazy, or farfetched. Some contemporary theories of criticism assert that the only reliable reading of a text is a misreading, and that the only existence of a text is given by the chains of responses it elicits. But this chain of responses represents the infinite uses we can make of a text (we can even use a Bible instead of a piece of wood in our fireplace), not the series of interpretations that depend on some acceptable conjectures about the intention of that text. How to prove that a conjecture about the intention of a text is acceptable? The only way is to check it against the text as a coherent whole. (…) I shall deal later with my negative realism but already in The Role of the Reader I was seeing the work of art as something that can say “no” to certain interpretations. In this book I also proposed the idea of a Model Reader, who is not the empirical one but rather the one postulated by the textual strategy and I also drew a distinction between the intention of the (empirical) author, the intention of the (empirical) reader and the intention of the text, the only one that becomes the object of a semiotic inquiry. (…) In developing my research, I came across Charles Sanders Peirce. I had known something about Peirce since my university years (…) but I started studying him in the Sixties when I found scattered but illuminating references to him in the writings of Roman Jakobson.

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

I worked intensely on Peirce from the beginning of the Seventies, also organizing courses and seminars about him at my faculty in Bologna and creating a sort of active Peircean school. The encounter with Peirce marked the end of my brief structuralist period. (…) My critique of structuralism appeared in a book from 1968, La Struttura Assente (The Absent Structure), a work that already betrayed the influence of Peirce, and in which I offered a critique of the positions of Lévi-Strauss, Lacan, Derrida, and Foucault. So, La Struttura Assente gradually became another book, A Theory of Semiotics (1976), which I wrote directly in English and then translated back into Italian as the Trattato di semiotica generale. This work contained the germ of all my subsequent research and marked the start of my proposal for a concept of the encyclopedia. In particular this was dominated by the Peircean concept of interpretation. Peirce defined semiotics as the discipline concerned with all the varieties of semiosis, and by semiosis he meant “an action, an influence, which is, or involves, a cooperation of three subjects, such as a sign, its object and its interpretant, this three-relative influence not being in any way resolvable into action between pairs”. The interpretant is that which the sign produces in the quasi-mind of the interpreter. Thus a sign is interpreted by another sign which in its turn will be interpreted by another sign and so on, potentially ad infinitum, through an unlimited process of semiosis. In the early Eighties, Einaudi had begun to publish an Enciclopedia (which then came out in sixteen volumes) that was limited to treating in an extremely broad fashion some concepts chosen as representative of the state of the natural and human sciences. The encyclopedia entries were thus very long and could amount to forty or so pages each. I had been assigned the entries sign, meaning, symbol, metaphor and code (and these texts were then reviewed, expanded and made into a book, Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language, 1984) (…). Another problem I have persistently worked on is the difference between a general semiotics and specific semiotics. The problem raised its head, for me, when in 1974 they held the First Congress of the International Association for Semiotic Studies, in Milan. The idea of an international association of scholars of semiotics began to coalesce during an initial encounter in Kazimierz (Poland) in 1966. Then various scholars (including Roman Jakobson, Émile Benveniste, Roland Barthes, Julia Kristeva, Thomas A. Sebeok and Algirdas J. Greimas) met up again in Paris in 1969 where they founded the International Association for Semiotic Studies. On that occasion it was decided to adopt the term semiotics (semiotics), used by Peirce and by other Russian- and English-speaking authors (Morris, for example), in preference to the term semiologia (sémiologie), widespread in other linguistic areas. (…) But the choice of semiotics, supported by Jakobson, also aimed at establishing the notion that the field of studies concerning the sign went beyond linguistics. Thus I became more and more convinced that “semiotics” is not the name of a single science or discipline, but rather that of a department or a school — just as there is no single science called “medicine” but instead “schools of medicine”, in the academic sense of the expression. In a school of medicine we have surgery, biochemistry, dietetics, immunology, psychiatry and so on (and sometimes even acupuncture and homeopathy). In such a school, experts in a given branch tend more and more not to understand the purposes and the language of other specialists but, in spite of such discrepancies, they can all work together because they have a common object, the human body, and a common purpose, its health. Semiotics is perhaps something similar, a field in which different approaches have, at the highest level of generality, a common object: semiosis. (…)

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

Keeping faith with the project for a general semiotics, for a long time I worked on the problem of meaning, and I have devoted many of my writings to this. In fact, I dare say that the debate on meaning, my polemic against the notion of the dictionary and my theory of the encyclopedia represent the most important contribution I have made to semiotic studies. (…) The notions of dictionary and encyclopedia have been used for some time in semiotics, linguistics, the philosophy of language and the cognitive sciences, not to mention computer science, to identify two models of semantic representation, models that in turn refer back to a general representation of knowledge and/or the world. In defining a term (and its corresponding concept), the dictionary model is expected to take into account only those properties necessary and sufficient to distinguish that particular concept from others; in other words, it ought to contain only those properties defined by Kant as analytical. According to such a perspective a definition does not assign to the dog the properties of barking or being domesticated: these are not considered as necessary properties and part of our knowledge of a language but of our knowledge of the world. They are therefore matter for an encyclopedia. (…) Hence the idea of an encyclopedia structured like a labyrinth, an idea that already appeared in d’Alembert in the “Preliminary Discourse” to the Encyclopédie. (…) My notion of encyclopedia was dominated by the Peircean principle of interpretation and consequently of unlimited semiosis. Every expression of the semiotic system is interpretable by other expressions, and these by others again, in a self-sustaining semiotic process, even if, from a Peircean point of view, this series of interpretants generates habits and hence modalities of transformation of the natural world. Every result of this action on the world must, however, be interpreted in its turn, and in this way the circle of semiosis is on the one hand constantly opening up outside of itself and on the other it is constantly reproducing itself from within. Furthermore, the encyclopedia generates ever new interpretations that depend on changing contexts and circumstances (…). So, in various books, I developed the notion of encyclopedia, like a galaxy of knowledge that does not take the form of a tree but a network. An illuminating idea had come to me, already in A Theory of Semiotics, from a model suggested by M. Ross Quillian, and later by the idea of a rhizome, suggested, albeit in a decidedly metaphorical way, by Deleuze and Guattari. Every point of the rhizome can be connected to any other point; the rhizome is anti-genealogical (it is not a hierarchized tree); it is susceptible to modification, according to the growth of our knowledge; a global description of the rhizome is not possible, either in time or in space; the rhizome justifies and encourages contradictions; if every one of its nodes can be connected with every other node, from every node we can reach all the other nodes; only local descriptions of the rhizome are possible and every local description tends to be a mere hypothesis about the network as a whole. Within the rhizome, thinking means feeling one’s way by conjecture. In this sense the encyclopedia is potentially infinite because it is in movement, and the discourses we construct on its basis constantly call it into question.

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

I have devoted many texts to the problem of fakes, from an early essay on forgery in the Middle Ages to a more substantial chapter in The Limits of Interpretation, and to a lecture in 1995 (now in On Literature) in which I dealt with the “power of falsehood”, that is, the way in which many historical fakes, from Prester John’s letter to the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion, have produced real historical events, sometimes in a positive way, sometimes tragically. Besides these essays, many of my novels have to do with the production of a fake, whether in the form of an invented plot (as in Foucault’s Pendulum and in The Prague Cemetery) or, as in Baudolino, in the figure of a creative and likeable forger who inspires many of the deeds of Frederick Barbarossa. Even if I had never dealt with the problem of truth in an explicit way, my interest in forgery was undoubtedly due to my idea that signs are those instruments that make it possible to tell lies or in any case to say what is not the case. But I think that it is impossible to speak of fakes if one does not have an underlying criterion for truth. Certainly, in a semiotics that favours interpretations more than the correspondence between signs and real objects or facts, one might think (as many of my critics have done) that I do not believe in the possibility of reaching any truth. I would first of all point out that I follow the Peircean principle according to which we produce interpretations and interpretations of interpretations, but the process of unlimited semiosis stops when we produce a habit that allows us to come to grips with reality (…). At that moment we realize that our interpretations are “good” and that we have reached some truth – even though such certainty is mitigated by the awareness that every discovery of a truth is subject to the principle of fallibilism. This implicit notion of truth is at the basis, as I have already said, of the idea that, while it is not possible to say when an interpretation is correct or is the only one possible, it is always possible to say when it is untenable. (…)

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

What are the inter-subjective criteria that allow us to define that particular combination of cards as off the wall? What criterion allows us to distinguish between dreams, poetic inventions and acid trips? (…) While I may use (scill. a screwdriver) to scratch my ear, which is at least possible but inexpedient, I cannot use it to transport a liquid as I could do with a glass. My remarks are not trivial at all even though they seem like mere truisms: what they mean is that a screwdriver responds positively (so to speak) to many of my possible interpretations, but in certain cases it says “no”. This sort of refusal opposed by the objects of our world is the basis of my prudent idea of a Negative Realism. (…) In Kant and the Platypus I called these terrible forces the hard core of Being. In speaking of a “hard core” I did not mean something like a “stable kernel” which we might identify sooner or later, not the Law of Laws, but, more prudently, lines of resistance that render some of our approaches fruitless. It is precisely our faith in these lines of resistance that also ought to guide the discourse on hermeneutics, because, if we assumed that one can say anything and that “anything goes”, the intellectual and moral tension that guides our continual interrogation of the World (even if we consider Being as something that continually vanishes and escapes our grasp) would no longer make sense. We should in any case admit the presence of that Something, even though that Something shows up as mere absence. (…) The fact that a technology, which by definition alters the limits of nature, is required in order to violate them means that the limits of nature exist. To state that there are lines of resistance merely means to say that, even if it appears only as an effect of language, Being is not an effect of language in the sense that language freely constructs it. The appearance of these Resistances is the nearest thing that can be found, before any First Philosophy or Theology, to the idea of God or Law. Certainly it is a God who manifests himself as pure Negativity, pure Limit, pure “No”, that of which language cannot or must not talk. In this sense it is something very different from the God of the revealed religions, or it assumes only His severest traits, those of the exclusive Lord of Interdiction, incapable of saying so much as “go forth and multiply”, but bent solely on repeating “thou shalt not eat from this tree”. This idea of lines of resistance, whereby something that does not depend on our interpretations challenges them, can represent a form of Minimal or Negative Realism according to which facts, while they certainly do not tell me when I am right, frequently tell me that I am wrong. (…) But we have the experience of an undeniable Limit before which our languages evaporate into silence, and that is the experience of Death. We question the World in the certainty, after thousands of years of experience, that all men are mortal, and Death is the Limit after which all interpreting initiatives vanish. Therefore, in knowing for sure that there is at least one limit that challenges the infinite progress of our interpretation, we are encouraged to persist in suspecting that there are other limits to the freedom of our conjectures. (…) If the continuum itself has lines of tendency, we are not entitled to say whatever we like. There are directions, maybe not compulsory directions, but certainly directions that are forbidden. There are things we cannot say. It doesn’t matter if these things were once said. We subsequently “banged our heads into” evidence that convinced us that we could no longer say what we formerly said. If so, Being may not be comparable to a one-way street but to a network of multi-lane freeways along which one can travel in more than one direction; but despite this some roads will nonetheless remain dead-ends. (…)

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

I consider myself a philosopher, even though I have written about many other topics; and I am certainly a philosopher who has also written seven novels. This last fact, given its dimensions and the time it took me from the end of the Seventies until today, cannot be considered a marginal accident. (…) I should say that, when I started to write The Name of the Rose, even though I used a lot of medieval philosophy texts, I did not think there was any link between my literary and academic writing. In fact I took my narrative adventure as a vacation. I was certainly aware of the fact that, in narrating, I was dealing with philosophical questions, but they were questions that my philosophy could not answer. On the jacket flap of the first Italian edition it was written, in conclusion: “If the author has written a novel it is because he has discovered, in his maturity, that what you cannot theorize about, you must narrate”. By paraphrasing Wittgenstein I could have written: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must narrate”. So I did not think of my novels as a demonstration of some philosophical theory. I knew that these works were often inspired by philosophical debates, but these could be mutually contradictory and, in narrating, I brought those contradictions into play. It then happened that many of my readers found philosophical positions in my novels: I accepted those readings but without approving or rejecting them, starting from the principle that sometimes a text is more intelligent than its author and says things that the author had not thought of yet. In any case I admit that in The Name of the Rose there is a debate on the problem of truth (but in the way this might have been seen by a fourteenth-century follower of Occam who was in crisis); in Foucault’s Pendulum there is a polemic against occultist thought and the various conspiracy syndromes; in The Prague Cemetery conspiracy theory is again the subject as I try to show the folly of anti-Semitism; The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana deals with questions about memory today studied by cognitive sciences; The Island of the Day Before has fun taking a new look at the various philosophies of the Baroque period and the situation of a universe without limits that is born with the discoveries of the new astronomy; Baudolino is an implicit reflection on the relationship between truth and the lie; and finally Numero Zero is an implicit debate about journalism and factual truth. (…)

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

When interviewers ask me “How did you write your novel?”, I usually cut them short and reply: “From left to right.” But this is a joke. In fact after my attempts at fiction I realized that a novel is not just a linguistic phenomenon. A novel (like every narrative we perform every day, explaining for instance why we arrived late that morning) uses words to convey narrated facts. Now, as far as fictional facts are concerned, the facts, or the story, are more important than words. Words are fundamental in poetry (and this is why poetry is so difficult to translate, because of the difference of sounds between two different languages). Thus in poetry it is the choice of the expression that determines the content. In prose the opposite happens: it is the world the author chooses, and the events that happen in it, that dictate rhythm, style, and even verbal choices. This is why in all of my novels my first endeavor was to design a world, and to design it as precisely as possible, so that I could move around in it with total confidence. For The Name of the Rose I drew hundreds of labyrinths, and plans of abbeys. I needed to know how long it would take two characters to go from one place to another while conversing. And this also dictated the length of the dialogues. For Foucault’s Pendulum I spent evening after evening, right through to closing time, in the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, where some of the main events of the story took place. In order to talk about the Templars I went to visit the Forêt d’Orient in France, where there are traces of their commanderies (which are vaguely alluded to in the novel). In order to describe Casaubon’s night walk through Paris, from the Conservatoire to Place des Vosges and then to the Eiffel Tower, I spent several nights between 2 am and 3 am walking along and dictating everything I could see into a pocket tape-recorder, so as not to get the street-names and intersections wrong. For The Island of the Day Before I naturally went to the South Seas, to the precise geographical location where the book is set, to see the colors of the sea, of the sky, of the fish and the corals — at various times of day. But I also worked for two or three years on drawings and small models of ships of the period, to find out how big a cabin or cubby-hole was, and how one could move from one to the other. Probably I started thinking of Baudolino because for a long time I had wanted to visit Istanbul, and the beginning and the end of my novel are set in that city. Once this world has been designed, the words will follow and they will be (if all goes well) those that that world and all the events that take place in it require. (…)

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

Another feature of my poetics is that the writer must comply with some constraints. For instance one of the constraints of Foucault’s Pendulum was that the characters had to have lived through 1968, but since Belbo then writes his files on computer — something that also plays a formal role in the whole story, since it partly inspires its aleatory and combinatory nature — the final events absolutely had to take place between 1983 and 1984 and not before, since the first personal computers with word-processing programmes went on sale in Italy only in 1983. In order to make all that time elapse from 1968 to 1983 I was forced to send Casaubon somewhere else. Where? My memories of some magic rituals that I had witnessed in Brazil led me there. This was the reason for what many people thought was an overly long digression, but was essential for me, because it allowed me to have one character, Amparo, experience something in Brazil, while that same something would happen to the other characters in the course of the book. In The Island of the Day Before the historical constraints were based on the fact that I needed Roberto to take part as a young man in the siege of Casale, to be present at Richelieu’s death, and then arrive at his island after December 1642, but not later than 1643, the year in which Tasman went there, even though this was some months earlier than the time in which my story was set. But I could set the story only between July and August because that was the period when I saw the Fiji islands, and a ship took several months to get there: this explains the mischievous novelistic insinuations that I make in the final chapter, to convince myself and the reader that perhaps Tasman had come back later to that archipelago without saying anything to anybody. Here one sees the heuristic usefulness of constraints that force you to invent silences, conspiracies, and ambiguities. Why all these constraints? Was it really necessary for Roberto to be present at Richelieu’s death? Not at all. But it was necessary for me to set myself constraints. Otherwise the story could not have gone along under its own steam. Still on the subject of constraints, the finale of Baudolino had to take place in 1204, because I wanted to narrate the conquest of Constantinople. But Prester John’s letter (which in my story is forged by Baudolino) is first mentioned around 1165. Why then did Baudolino not persuade Frederick Barbarossa to set off immediately for Prester John’s kingdom? Because I had to have him coming back from the kingdom only in 1204. What did I have to make Baudolino do in that interval of almost four decades? I made him constantly delay his departure. At the time it seemed like a waste to me, I had to insert a series of temporary stop-gaps into the story in order to arrive finally at that damned date of 1204. And yet, in doing so, I created the desire and the spasm. Baudolino’s desire for Prester John’s kingdom grows, as it does in the reader’s eyes, too (I hope). Once more the advantages of constraints. Narrators do not want to be free to invent anything they want. The construction of a world and the choice of some constraints obliges them to follow the internal logic of the story and to a certain extent the logic of the characters. These are the principles of my narrative and I think they are or should be common to every narrator. That’s why from fictions invented without any philosophical program, one can draw at least some aesthetic and semiotic laws (…).

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

Until the age of fifty, and throughout all my youth, I dreamt of writing a book on the theory of comedy. Why? Because every book on the subject has been unsuccessful. Every theoretician of comedy, from Freud to Bergson or Pirandello, explains some aspect of the phenomenon, but not all. This phenomenon is so complex that no theory is, or has been thus far, able to explain it completely. So I thought to myself that I would like to write the real theory of comedy, and I have written a few essays on comic and humour. But then the task proved desperately difficult. Maybe it is for this reason that I wrote The Name of the Rose, a novel that deals with the lost Aristotelian book on comedy. It was a way to tell as a story what I was unable to say in philosophical terms. Once again, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must narrate”. In ancient philosophy it was said (and Rabelais repeated this) that laughter was the proprium of men, that is, only humans have the prerogative of laughter. Animals are bereft of humor. Laughter is a typically human experience. We think that this is linked to the fact that we are the only animals who know they must die. The other animals can understand it only at the moment they die, but they are unable to articulate anything like the statement “We are all mortal”. Humans are able to do this, however, and that is probably why there are religions and rituals. But the real point is that, since we know that our destiny is death, we laugh. Laughing is a quintessentially human way to react to the human sense of death. In this way comedy becomes a chance to withstand tragedies, to limit our desires, to fight against fanaticism. Comedy (I am indirectly quoting Baudelaire) throws a diabolical shade of suspicion upon every proclamation of a dogmatic truth. Preparation for death consists essentially in convincing yourself gradually that — as it says in Ecclesiastes — all is vanity. Yet, despite this, even the philosopher acknowledges one painful disadvantage of death. The beauty of growing and maturing is realizing that life is a marvelous accumulation of knowledge. We call this experience, and so in times gone by the elders were considered the wisest of the tribe, and their task was to pass on their wisdom to their children and grandchildren. It is a wonderful feeling to realize that every day you learn something more, that your errors of the past have made you wiser, and that your mind (while perhaps your body gets weaker) is a library that grows larger every day with the addition of a new volume. I am one of those people who don’t miss their youth, because today I feel more fulfilled than ever. But the thought that all that experience will be lost at the moment of my death is a cause of suffering. The thought that those who come after me will know as much as I do, and even more, does not console me. It’s like burning down the Library of Alexandria or destroying the Louvre... We remedy this sadness by writing, painting, or building cities. Yet, no matter how much I pass on by writing about myself, or just by writing, even if I were Plato, Montaigne, or Einstein, I can never transmit the sum of my experience — for example, my feelings on seeing a beloved face or a revelation I have had on watching a sunset (…).

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

This is the true disadvantage of death, and even philosophers have to admit that there is something disagreeable about death. How to get around this problem? By winning immortality, some say. It is not for me to discuss whether immortality is a dream or a possibility, however small, whether it’s possible to live to over a hundred and fifty, whether old age is merely an illness that can be prevented. I limit myself to admitting the possibility of a very long or an endless life, because only in that way can I reflect upon the advantages of death. If I could choose, I’d want to live, let’s say, ad infinitum. But it is on thinking of myself not at a thousand but merely at two hundred that I begin to discover the disadvantages of immortality. If it were granted only to me, I would witness the disappearance, one by one, of my dear ones, my own children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. The aftermath of suffering and nostalgia that would accompany me in this protracted old age would be unbearable. And what if I realized I was the only one with memories in a world of scatterbrains who have regressed to prehistoric levels, how could I bear my intellectual and moral solitude? It would be even worse if the growth of my personal experience was slower than that of the collective experience, and I had to live with my modest, dated wisdom in a community of young people who surpassed me intellectually in every way. But it would be worse still if immortality or an incredibly long life were granted to all. We would live in a world overcrowded with people over a hundred (or a thousand) years of age who rob the younger generations of vital space and I would find myself plunged into an atrocious struggle for life, in which my descendants would wish me finally dead. And who can say I wouldn’t get bored with all the things that in my first hundred years were a source of wonder, amazement, and the joy of discovery? Would I still take pleasure from reading the Iliad for the thousandth time or from listening uninterruptedly to the Well-Tempered Clavier? Would I still be able to bear a dawn, a rose, a meadow in bloom, or the taste of honey? I begin to suspect that the sadness that overcomes me when I think that, by dying, I would lose all my treasure of experience is much like the feeling I get when I think that, by surviving, this oppressive and moldy experience would begin to get on my nerves. Perhaps it’s better to carry on, for the years that might be granted me, leaving messages in bottles for those who will come after me, as I wait for what Saint Francis called Sister Death. (…)

Brief biography

Excerpts from an intellectual autobiography

Umberto Eco knew how to inhabit many worlds — academia and popular culture, philosophy and fiction — with the rigor of a philologist and the lightness of a melancholy irony. He left behind an intellectual legacy built on method, curiosity, and a passion for knowledge understood as both the demystification of ideology and a practice of freedom.

Born in Alessandria to Rita and Giulio Eco, Umberto Eco (1932–2016) has been one of the most influential intellectuals of the late twentieth century. His education was rooted in the philosophical tradition of Turin, particularly in the school of Luigi Pareyson, under whose supervision he graduated in 1954 with a thesis on Thomas Aquinas. The Middle Ages would remain a constant in his thought — not only as a field of study, but as a symbolic workshop of narrative structures, mythologies, and worldviews.

With the seminal Opera aperta (The Open Work, 1962), Eco inaugurated a new approach to the interpretation of art and literature, differing from the still prevalent teachings of Benedetto Croce, in dialogue with the neo-avant-garde, information theory, and structuralist thought. This was followed by other foundational studies such as La struttura assente (The Absent Structure, 1968), Trattato di semiotica generale (A Theory of Semiotics, 1975), and Lector in fabula (1979). Building on the semiotic theories of American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, these works established Eco’s international reputation as a theorist of signs, interpretation, and communication processes (I limiti dell’interpretazione — The Limits of Interpretation, 1990). Eco believed that reality exists independently of us, but that we can only access it through interpretative filters and textual mediation. In Kant and the Platypus (1997), this idea developed into a critique of both radical relativism and the dogmatism of naïve realism — a call for balance between the existence of an external world and the multiplicity of its interpretations. By excluding interpretations that are demonstrably false, we can approach reality through trial and error, guided by signs, concepts, and socially mediated languages.

Eco was also a pioneer in the study of mass media. In the 1950s, he worked as a cultural editor for RAI, Italy’s national broadcaster, where he encountered experimental artists and intellectuals such as composer Luciano Berio, with whom he collaborated on the programs of the Studio di Fonologia Musicale. This experience nurtured his interest in contemporary forms of communication and anticipated his involvement in Gruppo 63, the literary avant-garde movement that sought to transcend traditional narrative structures, echoing the ideas already explored in Opera aperta. His editorial work was equally crucial: beginning in the 1960s, he worked at the publishing house Bompiani, where he met his wife Renate, the mother of their children, Stefano and Carlotta. There, Eco helped modernize the catalogue and introduced some of the most important voices in contemporary philosophy and the humanities to Italian readers. This editorial and public-facing engagement fed his lifelong dialogue with mass culture, which he later cultivated with brilliance and irony through his long-running column La bustina di Minerva in L’Espresso, where he reflected with wit and precision on language, politics, culture, and technology.

Worldwide fame came in 1980 with The Name of the Rose — translated into over forty languages and published in more than sixty countries — a novel that fused medieval mystery, theology, semiotics, and detective fiction. A philosopher “who also happened to write seven novels,” Eco went on to publish Foucault’s Pendulum (1988), a dizzying journey through esotericism and conspiracy; The Island of the Day Before (1994), a baroque meditation on time, fiction, and science; Baudolino (2000), a wise and playful voyage into the fantastic Middle Ages; The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana (2004), a visual and autobiographical novel about memory as a cognitive filter; The Prague Cemetery (2010), a fierce historical critique of modern antisemitism; and Numero Zero (2015), a lucid analysis of the mechanisms of information — an early warning against the rise of fake news and the chaotic, authority-less encyclopedia of the web. Throughout his life, Umberto Eco reflected — seriously, but never solemnly — on the act of storytelling and the thousand ways of reading, dismantling, and reconstructing it. With sharpness and irony, he crossed genres, languages, media, and centuries of history and literature, suggesting countless ways to wander among books. His work teaches us that storytelling is not only about saying, but about choosing, composing, and sharing spaces of meaning — and that to truly read is, in itself, a revolutionary act of freedom.

Copyright 2017 Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois 60601, USA

I was born in Alessandria, in the north west of the Italian peninsula. From the character of my fellow citizens I have learned the virtue of skepticism: despite their origins and the prowess they showed in resisting the Emperor’s siege, they never had any enthusiasm for any heroic virtues. (…) Skepticism implies a constant sense of humor to cast doubt even on those things that people sincerely believe in. It could be that this explains many cases in which I have waxed ironical about, or even parodied, texts on which I had written with great conviction. Born in 1932, I was educated under the fascist regime. I couldn’t understand, but I understood everything in the space of a few minutes on 27 July 1943. On the previous day fascism had fallen, Mussolini had been arrested and that morning, all of a sudden, newspapers I had never seen before appeared on the newsstands. Each one carried an appeal signed by the various parties, which were celebrating the end of the dictatorship. You didn’t have to be particularly smart to realize that those parties had not been formed overnight, they must have existed before, but evidently in clandestine form. I suddenly realized the difference between dictatorship and democracy and that, at eleven years of age, marked the beginning of my repugnance for any form of fascism.

My interest in philosophy began in high school, thanks especially to an extraordinary teacher, Giacomo Marino, who, along with history and philosophy, talked to us about literature, music and psychoanalysis. Together with Marino, Delmo Maestri and Giancarlo Lunati, two friends four years older than me (and who graduated when I started as a freshman), had a great influence on my philosophical development (…). But as soon as I arrived at Turin University I came into contact with other schools of thought. The teaching staff was made up of a group of philosophers who were very different from one another: Augusto Guzzo, who was generally classified as a Christian spiritualist although he defined himself as an Augustinian idealist (apart from his own ideas, he was also a masterful popularizer of other people’s ideas); Nicola Abbagnano, who was considered the leader of a “positive existentialism”, but in reality tended more and more towards certain trends in American philosophy and in any case was the head (also in terms of academic politics) of what was then defined as Neo-Enlightenment; Norberto Bobbio under whose supervision I sat an exam on Rousseau before he wrote in 1955 a book that greatly influenced me, Politics and Culture; and Carlo Mazzantini, an outstanding medievalist (…). In my second year at Turin University Luigi Pareyson was appointed full professor of aesthetics. His lessons were fascinating, they were not theatrical like Guzzo’s, not skeptically ironic like Abbagnano’s, but extremely rigorous, of a lucid, brilliant pedantry. So I decided to do my doctoral dissertation with Pareyson on the problem of aesthetics in Aquinas. It was my way of understanding medieval philosophy while tackling contemporary problems in aesthetics at the same time.

In working on Aquinas my intention was to show that the ancient world and the Middle Ages had reflected on the beautiful and on art (albeit in ways that differ from modern and contemporary philosophy) and the task I set myself was to free the medieval thinker from all the Neo-Thomist interpretations that, in order to demonstrate their “modernity”, had tried to make him say what he had not said. In those same years this polemic came to coincide with certain events that changed my life. A militant Catholic and a national leader of the youth branch of Azione Cattolica known as Gioventù Cattolica, I was (together with my comrades) still influenced by the personalism of Emmanuel Mounier and Esprit, which led us to be, as they said in those days, “left-wing Catholics” — and in any event anti-fascists. So I was one of those “rebels” who in 1954 left the organization in protest against the support Pope Pius XII was giving to Luigi Gedda, the president of Azione Cattolica, who was leading the organization towards the far right. This matter, which many of my comrades of those days held to be solely political, was gradually turning into a genuine religious crisis for me. (…) The thesis had begun as an exploration of a territory I still considered to be contemporary and then, as the inquiry proceeded, the territory was objectified as a distant past, which I reconstructed with fondness and enthusiasm, but the way you do with the papers of a deceased person you have greatly loved and respected. And this result derived from my historiographical approach, where I decided to clarify every term and every concept found in the medieval texts with reference to the historical moment in which they were expressed. In order to be truly faithful to Aquinas, I restored him to his own time; I rediscovered him in his authentic appearance, in his “truth”. Except that his truth was no longer mine. All that I inherited from Aquinas was his lesson of precision and clarity, which remained exemplary.

(…) At the end of 1954 I had moved to Milan when I got a job in the cultural program section of the newborn television service. In television I came into contact with a communicational experience that was new at the time, and I had published in the Rivista d’estetica an article on television and aesthetics. But this was not the only aspect of the mass media I was interested in: I was also into comic books and other aspects of popular art and in the early Sixties I had published a piece in praise of Schultz’s Peanuts that was translated into English many years after by the New York Review of Books. (…) In those corridors I chanced to bump into Igor Stravinsky and Bertolt Brecht. In short, it was an experience that was fun more than anything else and left me a lot of free time in which to continue my studies. I broke off my work in television to do my military service and immediately after that I started work as an editor with the Bompiani publishing house, then run by the great publisher Valentino Bompiani. (…) The seventeen years spent at Bompiani were valuable for my philosophical activity. First of all, almost immediately the publisher put me in charge of the “Idee nuove” (New Ideas) series. It was a famous series that, even before World War II, and getting around fascist censorship, had published many important European authors, over and above the then dominant Crocean idealist tradition: it should suffice to mention names such as Spengler, Scheler, Simmel, Santayana, Jaspers, Abbagnano, Berdiaeff, Hartmann, Ortega y Gasset, Unamuno, Bradley, Windelband and Weber. When I took over the series, the Encyclopedia of Unified Science had just brought out an anthology of its principal texts. Among the authors I later had published I should mention works by Arendt, Barthes, Gadamer, Lotman, Paci, Merleau-Ponty, Goldmann, Whitehead, Husserl, Sartre, Hyppolite, Reichenbach, Tarsky and Baudrillard, as well as other Italian authors and various collections in Italian of the works of Charles S. Peirce. But in parallel with this series I had also started up a series that was to publish various works on cultural anthropology, psychoanalysis and psychology (Fromm, Kardiner, Jung, Binswanger and Margaret Mead). In subsequent years I also started up a series on semiotics that featured, as well as many Italian scholars, texts by Jakobson, Greimas, Lotman, Goffman. In the Seventies I also founded the magazine VS – Quaderni di Studi Semiotici (which is still published) in which I invited contributions from authors from various countries, published also in French and English. Working for a publishing house allowed you to consult all the book catalogs from a variety of countries: so working for a publisher was like living in an extraordinarily up-to-date library. (…)

To understand the birth of The Open Work I have to take a step back and return to the four years I spent in television. At that time the top floor of the radio and television building housed the music phonology laboratory run by great musicians such as Luciano Berio and Bruno Maderna, who conducted the first experiments in electronic music. The laboratory was frequented by musicians such as Boulez, Stockhausen and Pousseur and the encounter with the problems, the practices, and the theories of post-Webern music was fundamental for me, also because those musicians were interested in the relationship between the new music and linguistics. It was through Berio that I then met Roland Barthes and Roman Jakobson, and it was in Berio’s magazine, Incontri musicali, that were published discussions between a structuralist linguist like Nicholas Ruwet and a musician like Pousseur and I began to publish the first essays of the book that in 1962 would become The Open Work. Finally, in Milanese circles the new magazine Il Verri had come into being while the meetings and discussions on art and literature that were to give rise to the Gruppo 63 — a community of writers and artists of the new avant-garde — were already taking place. So that was the situation for a young scholar of aesthetics, who since high school had had contacts with the first “modern” poetics, and who found himself stimulated both by the practices of the avant-garde and those of mass communications. I did not maintain that these two aspects of my research were separate, and I was looking for a point of fusion between the study of “high” art and that of the art held at the time to be “low”. And if the moralists who were insensitive to the new times accused me of studying Mickey Mouse as if he were Dante, I replied that it is not the subject but the method that defines the correctness of research (and, moreover, a good use of method makes it clear why Dante is more complex than Mickey Mouse and not the other way round). Pareyson’s thinking had helped me to distance myself definitively from Croce’s aesthetics. (…) There was, however, an aspect of Pareyson’s aesthetics that I did not accept (and it was this divergence that provoked our long-lasting period of mutual incomprehension). Since Pareyson’s idea was that the theory of interpretation concerned not only artistic forms, but also natural ones, for him interpreting a form involved presupposing a Shaper [Figuratore] who has constituted the natural forms specifically as cues for possible interpretations. Conversely, I thought that the entire theory of interpretation could be “secularized” without a metaphysical recourse to the Shaper, who at best can be postulated as a psychological support for those who embark upon the adventure of interpretation. In any case, from Pareyson’s theory of interpretation I got the idea that, on the one hand, a work of art postulates an interpretative intervention; but, on the other hand, it exhibits formal characteristics in such a way as to stimulate and simultaneously regulate the order of its own interpretations. That is why, faced with the unavoidable presence of the form to be interpreted, years later I insisted on the principle that perhaps it is not always possible to say when one interpretation is better than others but it is certainly always possible to say when the interpretation fails to do justice to the interpreted object.

In 1962 in The Open Work I was advocating the active role of the interpreter in the reading of artistic texts (and not only verbal ones). In a way it was one of the first attempts to elaborate what was later defined as reception aesthetics or reader oriented criticism. (…) To say that the interpretations of a text are potentially unlimited does not mean that interpretation has no object. Even if we accept the idea of unlimited semiosis, to say that a text potentially has no end does not mean that every act of interpretation has a happy ending. This is why in The Limits of Interpretation (1990) I proposed a sort of Popper-like criterion of falsification whereby, while it is difficult to decide if a given interpretation is a good one, and which of two different interpretations of the same text is better, it is always possible to recognize when a given interpretation is blatantly wrong, crazy, or farfetched. Some contemporary theories of criticism assert that the only reliable reading of a text is a misreading, and that the only existence of a text is given by the chains of responses it elicits. But this chain of responses represents the infinite uses we can make of a text (we can even use a Bible instead of a piece of wood in our fireplace), not the series of interpretations that depend on some acceptable conjectures about the intention of that text. How to prove that a conjecture about the intention of a text is acceptable? The only way is to check it against the text as a coherent whole. (…) I shall deal later with my negative realism but already in The Role of the Reader I was seeing the work of art as something that can say “no” to certain interpretations. In this book I also proposed the idea of a Model Reader, who is not the empirical one but rather the one postulated by the textual strategy and I also drew a distinction between the intention of the (empirical) author, the intention of the (empirical) reader and the intention of the text, the only one that becomes the object of a semiotic inquiry. (…) In developing my research, I came across Charles Sanders Peirce. I had known something about Peirce since my university years (…) but I started studying him in the Sixties when I found scattered but illuminating references to him in the writings of Roman Jakobson.

I worked intensely on Peirce from the beginning of the Seventies, also organizing courses and seminars about him at my faculty in Bologna and creating a sort of active Peircean school. The encounter with Peirce marked the end of my brief structuralist period. (…) My critique of structuralism appeared in a book from 1968, La Struttura Assente (The Absent Structure), a work that already betrayed the influence of Peirce, and in which I offered a critique of the positions of Lévi-Strauss, Lacan, Derrida, and Foucault. So, La Struttura Assente gradually became another book, A Theory of Semiotics (1976), which I wrote directly in English and then translated back into Italian as the Trattato di semiotica generale. This work contained the germ of all my subsequent research and marked the start of my proposal for a concept of the encyclopedia. In particular this was dominated by the Peircean concept of interpretation. Peirce defined semiotics as the discipline concerned with all the varieties of semiosis, and by semiosis he meant “an action, an influence, which is, or involves, a cooperation of three subjects, such as a sign, its object and its interpretant, this three-relative influence not being in any way resolvable into action between pairs”. The interpretant is that which the sign produces in the quasi-mind of the interpreter. Thus a sign is interpreted by another sign which in its turn will be interpreted by another sign and so on, potentially ad infinitum, through an unlimited process of semiosis. In the early Eighties, Einaudi had begun to publish an Enciclopedia (which then came out in sixteen volumes) that was limited to treating in an extremely broad fashion some concepts chosen as representative of the state of the natural and human sciences. The encyclopedia entries were thus very long and could amount to forty or so pages each. I had been assigned the entries sign, meaning, symbol, metaphor and code (and these texts were then reviewed, expanded and made into a book, Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language, 1984) (…). Another problem I have persistently worked on is the difference between a general semiotics and specific semiotics. The problem raised its head, for me, when in 1974 they held the First Congress of the International Association for Semiotic Studies, in Milan. The idea of an international association of scholars of semiotics began to coalesce during an initial encounter in Kazimierz (Poland) in 1966. Then various scholars (including Roman Jakobson, Émile Benveniste, Roland Barthes, Julia Kristeva, Thomas A. Sebeok and Algirdas J. Greimas) met up again in Paris in 1969 where they founded the International Association for Semiotic Studies. On that occasion it was decided to adopt the term semiotics (semiotics), used by Peirce and by other Russian- and English-speaking authors (Morris, for example), in preference to the term semiologia (sémiologie), widespread in other linguistic areas. (…) But the choice of semiotics, supported by Jakobson, also aimed at establishing the notion that the field of studies concerning the sign went beyond linguistics. Thus I became more and more convinced that “semiotics” is not the name of a single science or discipline, but rather that of a department or a school — just as there is no single science called “medicine” but instead “schools of medicine”, in the academic sense of the expression. In a school of medicine we have surgery, biochemistry, dietetics, immunology, psychiatry and so on (and sometimes even acupuncture and homeopathy). In such a school, experts in a given branch tend more and more not to understand the purposes and the language of other specialists but, in spite of such discrepancies, they can all work together because they have a common object, the human body, and a common purpose, its health. Semiotics is perhaps something similar, a field in which different approaches have, at the highest level of generality, a common object: semiosis. (…)

Keeping faith with the project for a general semiotics, for a long time I worked on the problem of meaning, and I have devoted many of my writings to this. In fact, I dare say that the debate on meaning, my polemic against the notion of the dictionary and my theory of the encyclopedia represent the most important contribution I have made to semiotic studies. (…) The notions of dictionary and encyclopedia have been used for some time in semiotics, linguistics, the philosophy of language and the cognitive sciences, not to mention computer science, to identify two models of semantic representation, models that in turn refer back to a general representation of knowledge and/or the world. In defining a term (and its corresponding concept), the dictionary model is expected to take into account only those properties necessary and sufficient to distinguish that particular concept from others; in other words, it ought to contain only those properties defined by Kant as analytical. According to such a perspective a definition does not assign to the dog the properties of barking or being domesticated: these are not considered as necessary properties and part of our knowledge of a language but of our knowledge of the world. They are therefore matter for an encyclopedia. (…) Hence the idea of an encyclopedia structured like a labyrinth, an idea that already appeared in d’Alembert in the “Preliminary Discourse” to the Encyclopédie. (…) My notion of encyclopedia was dominated by the Peircean principle of interpretation and consequently of unlimited semiosis. Every expression of the semiotic system is interpretable by other expressions, and these by others again, in a self-sustaining semiotic process, even if, from a Peircean point of view, this series of interpretants generates habits and hence modalities of transformation of the natural world. Every result of this action on the world must, however, be interpreted in its turn, and in this way the circle of semiosis is on the one hand constantly opening up outside of itself and on the other it is constantly reproducing itself from within. Furthermore, the encyclopedia generates ever new interpretations that depend on changing contexts and circumstances (…). So, in various books, I developed the notion of encyclopedia, like a galaxy of knowledge that does not take the form of a tree but a network. An illuminating idea had come to me, already in A Theory of Semiotics, from a model suggested by Ross Quillian, and later by the idea of a rhizome, suggested, albeit in a decidedly metaphorical way, by Deleuze and Guattari. Every point of the rhizome can be connected to any other point; the rhizome is anti-genealogical (it is not a hierarchized tree); it is susceptible to modification, according to the growth of our knowledge; a global description of the rhizome is not possible, either in time or in space; the rhizome justifies and encourages contradictions; if every one of its nodes can be connected with every other node, from every node we can reach all the other nodes; only local descriptions of the rhizome are possible and every local description tends to be a mere hypothesis about the network as a whole. Within the rhizome, thinking means feeling one’s way by conjecture. In this sense the encyclopedia is potentially infinite because it is in movement, and the discourses we construct on its basis constantly call it into question.

I have devoted many texts to the problem of fakes, from an early essay on forgery in the Middle Ages to a more consistent chapter in The Limits of Interpretation, down to a conference in 1995 (now in my On Literature) in which I dealt with the “power of falsehood”, that is, the way in which many historical fakes, from Prester John’s letter to the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion, have produced real historical events, sometimes in a positive way, sometimes tragically. Besides this, many of my novels deal with the production of a fake, be it an invented plot (as in Foucault’s Pendulum and in The Prague Cemetery) or in Baudolino, where the hero is a creative and likeable forger who inspires many of the deeds of Frederick Barbarossa. Even if I had never dealt with the problem of truth in an explicit way, my penchant for forgeries was undoubtedly due to my idea that signs are those instruments that make it possible to tell lies or in any case to say what is not the case. But I think it is impossible to speak of fakes, if one does not have an underlying criterion for truth. Certainly in a semiotics that favors interpretations more than the correspondence between signs and real objects or facts, one might think (as many of my critics did) that I do not believe in the possibility of reaching any truth. I would first of all point out that I follow the Peircean principle according to which we produce interpretations and interpretations of interpretations, but the process of unlimited semiosis stops when we produce a habit that allows us to come to grips with reality (…). At this moment we realize that our interpretations were “good” and we have reached some truth – even though such a certainty is mitigated by the awareness that every discovery of a truth is subject to the principle of fallibilism. Such an underlying notion of truth is at the basis of my idea, as I have already said, that while it is not possible to say when an interpretation is correct or is the only one possible, it is always possible to say when it is untenable. (…)