Publishing

Publishing, like other intellectual professions, is a craft that operates as a workshop and as an infinite catalogue of the world, capable of filtering, recording and disseminating critical knowledge.

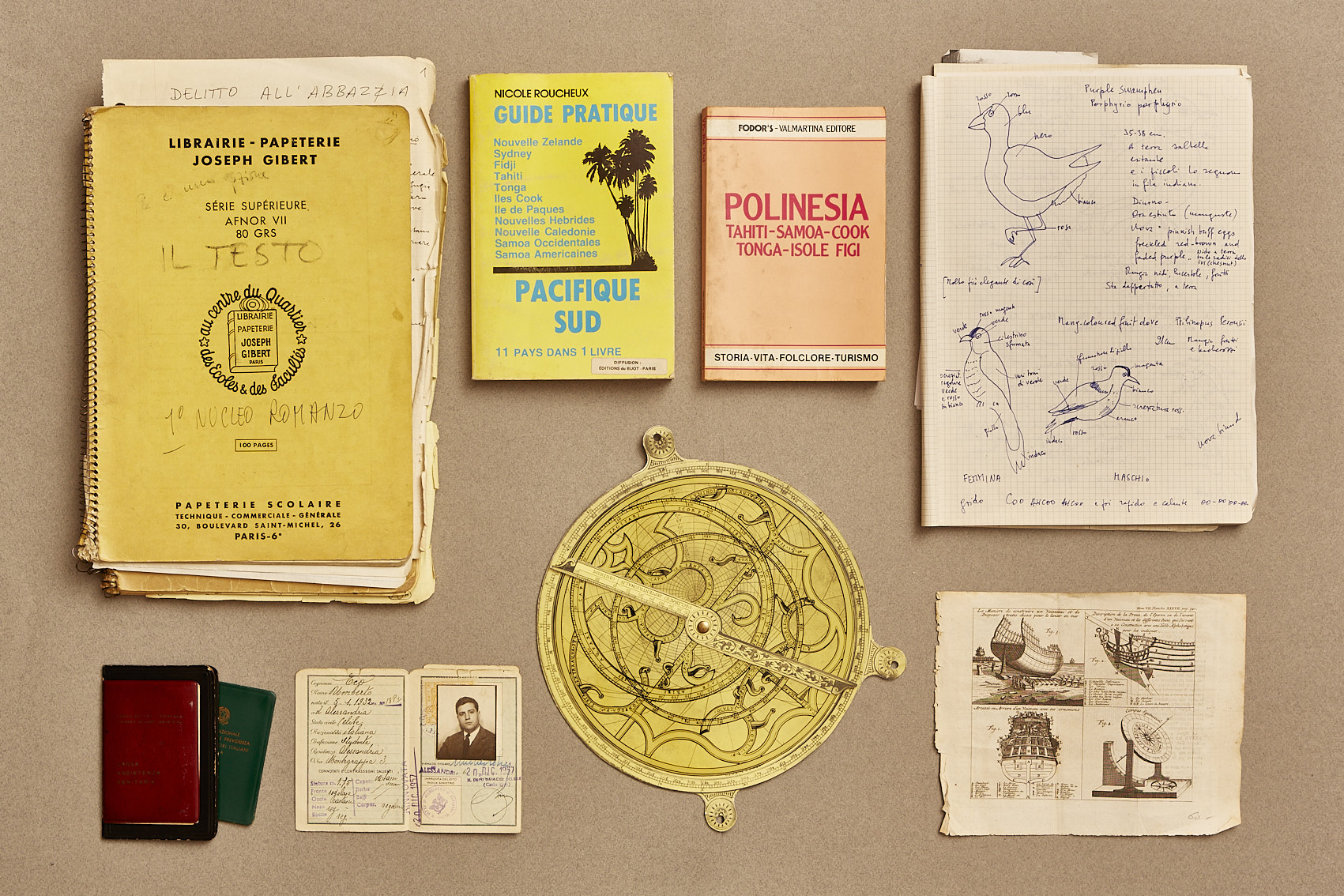

It was in 1959 that the publishing season proper began: having left RAI, Umberto Eco joined Bompiani as a publishing executive. It is no coincidence that the first work he worked on was an encyclopedia, the Storia figurata delle invenzioni (Illustrated History of Inventions), written together with his future wife Renate Ramge: the encyclopedic device remained his natural habitat, even before theory and long before fiction.

To tell the truth, it was Italo Calvino, who had thought of publishing Opera aperta as a single essay for Einaudi, who first intuited the theoretical strength and publishing potential of Eco's work. But in the meantime Valentino Bompiani wanted him in the editorial staff of the publishing house in Via Pisacane in Milan and integrated him into the publishing machine. Around him moved Enzo Paci, Roberto De Benedetti, Elio Vittorini, Giovanni Battista Zorzoli, Andrea Bonomi and Vittorio Di Giuro, to whom we owe the support for The Name of the Rose by Eco the novelist and his introduction to Valentino Bompiani's attention.

Eco's work focused particularly on the philosophical series Idee Nuove (New Ideas), a series that Eco inherited from Paci and which, even earlier, had roots in the philosophical tradition of Antonio Banfi. Between the 1960s and 1970s, McLuhan, Barthes, Jakobson, Lévi-Strauss, and Goodman arrived in the catalogue, bringing with them the horizon of contemporary human sciences.

It is within this framework that sections dedicated to the philosophy of language, formal logic, structural linguistics, and the sociology of communication are placed, expanding the field from philosophical thought to media theory and the sciences of signs. Here arrived the contemporary human sciences: phenomenology, philosophy of language, semiotics, linguistics, logic, sociology.

Within this framework fits Il campo semiotico (The Semiotic Field), a series directly linked to Eco's name, which introduced not only the great classics of the discipline — translated and made available to the Italian public — but also the texts of his academic students, including Daniele Barbieri, Giovanna Cosenza, Anna Maria Lorusso, Costantino Marmo, Siri Nergaard, Claudio Paolucci, Maria Pia Pozzato, Isabella Pezzini, Valentina Pisanty, Patrizia Violi, Ugo Volli. It is a true editorial laboratory of semiotics, in which the catalogue does not merely reflect a discipline but contributes to building it materially.

However, Eco was also the author of continuous forays into all areas of the publishing house, and particularly into fiction. The editorial office is a porous organism, and Eco moved through its departments with ease, going so far as to invent series such as "Amletica leggera" (Mafalda comics, early works by Woody Allen), in which editorial lightness becomes a tool for analyzing "domestic customs." After all, it is no coincidence that an editorial office, that of the fictional Garamond, is at the center of the plot of one of his most beautiful novels, Foucault's Pendulum, entirely built around the certainty of sources of knowledge.

It is also significant that his theoretical essays, faithful to an editorial tradition that does not want series editors and publishers to publish with their own imprints, appeared not in the series he directed but in Bompiani's Studi di critica letteraria (Studies in Literary Criticism), where they found a distinct placement while remaining within the same publishing house. Eco, as an author, would always remain faithful to Bompiani, with few exceptions: the entries in the Einaudi Encyclopedia, the volume Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language (Einaudi), and later, The Search for the Perfect Language and La filosofia e le sue storie (Laterza).

Alongside essays, fiction, and general interest books, Eco never abandoned the encyclopedic model. From the very beginning of his intellectual adventure, he contributed to the aesthetics entries of the Grande Enciclopedia Marzorati; he contributed to the lemma list and structure of the Einaudi Encyclopedia. In addition to the History of Inventions, he published How to Write a Thesis in Bompiani's Manuals series, a text that introduced generations of students to research and citation of sources: archiving, citing with full knowledge. The philosophy textbooks, published by Laterza, performed the same function of orientation among sources and certain knowledge.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Eco transferred this logic to digital. With Olivetti he experimented with the CD-ROM as a navigable form; with Danco Singer and the Espresso Group he created Encyclomedia; the History of European Civilization (2000–2015) is its paper version. It is the same workshop, with new tools.

Just as new are the hybrid narrative and editorial tools, embodied, for example, by his great passion for comics: from American and Argentine classics to the founding of Linus in 1965 — with the poetry of Peanuts strips and with Giovanni and Annamaria Gandini, Elio Vittorini, Oreste del Buono, Franco Cavallone, Salvatore Gregorietti — to Corto Maltese, Dylan Dog, and the novel The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, which interweaves text and images. Comics have always accompanied Umberto Eco's intellectual and professional journey.

The last innovative editorial gesture is the return to vegetable memory in the digital age. It dates from 2015: the founding of the publishing house La nave di Teseo with Jean Claude Fasquelle, Elisabetta Sgarbi, Mario Andreose, Furio Colombo and others to rescue Bompiani's legacy from absorption into other publishing brands. It is not a nostalgic act, but a gesture of coherence. La Nave di Teseo continues its journey to this day.

For Eco, publishing is both art and craft, a bricolage of knowledge in the noble sense given by Lévi-Strauss: arranging what exists to bring into being what does not yet exist. A work that holds together technology — from encyclopedic volumes to CD-ROMs, to digital infrastructures — and the passion for the book as object, which flows into bibliophilia and his extraordinary collection of antique volumes. It is the Semiological Library, curious, lunar, magical and pneumatic, today preserved at the Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, in the Eco Room, and accessible to everyone: not a mausoleum, but a public continuation of his editorial laboratory.